Centenary Stories

-

Claude Cunningham

“Diary” of a Student: Claude Cunningham (MSc Eng 1971)

In February 1967, aged 22, I travelled from what was then Rhodesia to Johannesburg to take a Graduate Diploma in Engineering (GDE) at the Wits Mining Department. There was an option to turn the GDE into an MSc in Engineering. Most of my letters home from this period were kept by my mother. Here are some extracts from the letters...

24 February 1967, Ernest Oppenheimer Hall. I wrote from my room in the brand-new hostel:

“As a post graduate, I have a very large room on the ground level, facing into the quadrangle. There are two large windows with Venetian blinds. The desk is the finest I have ever had, and there is plenty of room for storing things. There is no basin in the room, but there is a huge closet, more a dressing room, attached. A light comes on inside when I open the door, and you will be pleased to hear that they provide a huge covered garage for student cars.”

3 March: Trying to get a student loan:

“...rang up the Chamber of Mines today, but could not get past the personnel officer. He was most unhelpful, saying that they had awarded their two grants for 1967, and were not going to give any more.” But res life was looking good: “I seem to have got to know an awful lot of people this short week, and can see that I am likely to have a thoroughly good time here.”

18 March: I managed to get a bursary from JCI, with the understanding that I would “go through the mill of Mining Graduate, Shift Boss, etc, to finally arrive at the top ... The grant is worth my class and residence fees, plus R300 per year in 4 payments.”

My friend Grant Robinson and I planned to go “skin diving in Portuguese East Africa with a couple of women” over the Easter weekend – driving there in my mother’s old car, a 1962 Vauxhall VX4/90 called “Vicky”. Meanwhile I took my friend Jill to the Freshers’ Concert, wearing a new dinner jacket. “Jill was resplendent in a long, pink satin ball gown, and quite outshone (most of us thought) all the other girls.”

7 April:

“I was going to swot on Friday, but started off the evening by going to the Miners’ Smoker in the cricket pavilion, where we paid our 50c and then had unlimited quantities of beer. I had about 5 pints, then went back to hall for supper, feeling rather light-headed. During supper, I heard that one of the House Comm chaps was offering a free ticket to the Rag Coronation ball, as his girl had fallen ill at the last moment. I had a terrific rush around to find him, having decided I probably would not do much work that night anyway, and eventually tracked the ticket down ...” My chips were up with Jill, so I had to find another date at short notice!

16 April:

“I had a talk with Prof Plewman about my MSc thesis the other day, and he offered me an extremely interesting one he had just thought up, involving rock mechanics and theory of blasting. I will be thinking about it.”

A lot of partying followed. “I had to sluice several pounds of punch off the walls and the door, the result of all the splooshing.”

The JSI funding wasn’t going as far as I’d expected and I had my eye on a stereo tape recorder, which cost R320. I described its excellent features to my parents in the hope that they would help me buy it.

29 April: I went to the inter-varsity rugby versus Tukkies in Pretoria. “We all wore Wits shirts and blue and yellow hats, and kept up a terrific noise the whole time.”

10 May:

“The Cottesloe Room [a res social club] is consuming vast quantities of booze, and I opened an account at the Liquor Wholesalers for us. ... At the moment there are big preparations going on for Rag, on Saturday. They are building our float in the garage yard, so we all have to move our cars out, which is a nuisance, and all the activity is most distracting at this critical time.” A night was spent making paper flowers for the Rag float. “The procession was great fun. I wore an old hick straw hat, dirty jeans and my ‘Sex Symbol’ T shirt.”

3 June: I noted some of the political developments in the Middle East, Rhodesia and South Africa.

“The politics down here is enough to give you a pain. The whole economy is being sacrificed for Boer ideology. Here at Wits there is quite stiff resistance to the Nats, and they have something rather like Private Eye, called ‘Loo Wall’, which is posted up in the Union, and takes the Mickey out of them in an extremely funny way.”

24 June: “Exams loom large as life, and twice as difficult. I am rather worried about this lot, which are based on some rather hairy lectures.”

6 August: “I have spent most of my time reading for the thesis. It is amazing how stuff you think you’ll never master pans out easily when you really get down to it.”

I’d gone ahead and bought the tape recorder, and now started dreaming of an Olivetti typewriter with “a tabulator, different colour inks, a nice touch, and several useful keys”, as well as a Minolta camera “with through-the-lens light meter and wonderful focusing”. And a record player. Meanwhile the car required plenty of attention after some long journeys on bad roads. Petrol for a trip with friends to the Natal south coast worked out to “R2.80 each for both ways”.

Amid a steady flow of parties, the work was getting serious.

21 January 1968:

“I have been very busy this week, both designing and building and testing some specialised detonator firing equipment. It is quite successful, reducing the bursting time to within a fairly accurate margin of 800 millionths of a second. If I can reduce the margin slightly more, and I think I can, we will be able to do some very good tests using the high speed camera.”

29 January:

“On Thursday I took some perspex homolite plates to the CSIR, together with some seismic detonators and quite a few feet of explosive cord, and proceeded to do dynamic photoelastic studies of strain/ crack propagation using their high speed camera. ... [O]ur most exciting blast was an attempt to photograph a pre-split in homolite. ... we eventually got pictures of a split taking place: the first in the world! ... I’m now poised for the big dive before writing my thesis.”

4 August: I described a visit to Durban Deep.

“There we were shown some most interesting experimental work they have been doing in stoping. Alf [Brown, my MSc supervisor] designed the method five years ago, but red tape has rather held up its implementation. Basically, a huge, rigidly mounted drill is used to drill 100 foot holes parallel to the stope face. Two holes are drilled, at top and bottom, then loaded lightly, but coupled with water, and blasted. Using this method, no one ever has to go into the stope. It calls for terrific accuracy of drilling, but they are now constantly keeping within 6 inches of line over the length of the holes. In conventional stoping they have also been successful in using a form of presplitting, with slotted holes. It was a most interesting visit, and I think it showed the shape of things to come in the S African mining industry.”

A comment on salaries after some mine visits: “The mine certainly throws its money around - they pay their stopers up to R800 per month, and developers more than R1000!”

In October 1968 I started work at JCI.

-

Louise Grenfell

Louise Grenfell (BA 1988, HDipAdSoc 1989) writes:

I attended the University of the Witwatersrand from the beginning of 1985, till the end of 1988. During this time, I obtained a Bachelor of Arts in social work, and a post graduate higher diploma in advanced social work practice.

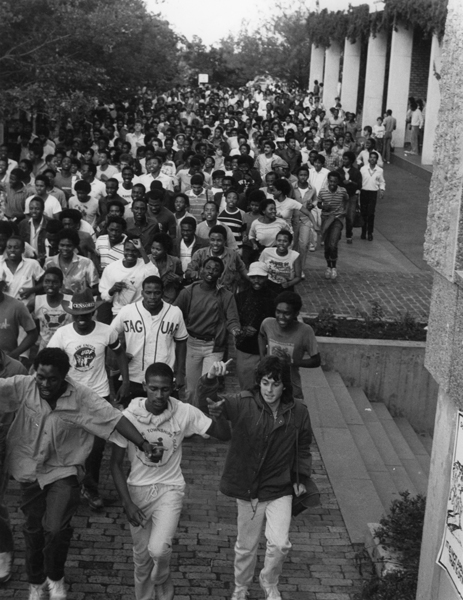

Wits opened up varied possibilities for me. Not only was I able to receive top-quality training in the valuable and essential discipline of social work, but I could also engage in a degree of political activism, against the oppressive apartheid system, and engage in different social activities. Our political activism brought us into direct conflict with police on campus, when they stormed across the library lawn to teargas us, beat us with batons, and shoot us with rubber bullets. Most of the policemen were younger than many of us students, with pimply skin, and closely shaven heads, sent into “battle”, with fear in their eyes, and batons in their hands, to defend an ideology which was indefensible.

The Academic Freedom March across Jan Smuts Avenue enraged the abusers of power, and their superiors, but we all stayed connected, and made our protest, arm in arm with cleaners, lectures, and students alike.

Campus life was never dull, and there was always something to get involved in, apart from lectures and social work practicals in the afternoons. I joined the Wits Explorers Club, which took us on real life adventures, rafting down the Tugela River on several occasions, and canoeing down the Kavango River for 10 days, on one occasion. On one of our Tugela trips, one of our rubber dinghy’s capsized, and we lost a cold box containing vital food supplies, when it sank to the river’s bottom. Some of our resourceful male colleagues duly plunged down to recover it, and we spent time drying out the soggy bread and packets of dried veggies and Toppers soya mince, at our overnight camping spot. Without these supplies, we would have gone hungry, and would not have been able to finish the trip.

On another occasion, our negotiations regarding permission and a nominal payment for us to travel down the river, through the land of the local tribal authority, had been completed, and we proceeded down the river, as usual. While traversing a particular section of the rapids, we suddenly came under “attack” by young residents, who pelted us with stones of varying sizes, injuring some of our members quite badly, despite the plastic helmets, and protective life jackets we wore, and oars we used to paddle, and deflect the stones, intermittently. At the overnight camping spot, along the river bank, we were attacked again, and whilst trying to defend ourselves, local children came and removed some of our belongings, including shoes, cameras and our car keys. Us women, being outnumbered by about 4 to 1 by our male colleagues, (with about 20 people in total), looked after the camp, whilst the guys went in search of our stuff. Rushing off with no shoes on, some of their feet got badly hurt, and they had to reconsider their strategy. Eventually, peaceful discussions revealed that some local teenagers were engaging in this misbehaviour, and they were duly brought to order by their embarrassed elders. We recovered most of our belongings, and continued down the river the next day.

It must also be stated, that a few of our more immature male explorers decided it was their primary duty, to initiate new women members, by hitting us on our helmets with their paddles, saying, “paddle, Doris”, and even holding us under the water, whenever our dinghy’s dumped us in the water, going through a rapid. We also discovered how obsessed some guys get about descriptions of their bowel movements, and they demanded such descriptions from us too. They were so relentless, that we just had to make up stories to shut them up.

The Okavango trip was really memorable. We set out in some fiberglass canoes, and some traditional Makhoro canoes, which are carved out of one ironwood tree trunk or branch, and are obviously long and narrow, being very difficult to balance in the water. We used roughly carved paddles, which gave some members serious blisters, as we made our way down the Kavango River to Chief’s Island. It took us five days, camping under the Sausage pod trees each night, and eating smoked fish we had caught on hand lines. We had an excellent guide, who was very experienced, and taught us so much along the way. Each night after supper, I would take a bucket to wash in, away from the camp, until once coming across some lion tracks, reminding me there weren’t any fences in that wild place, and all the animals roamed around freely. The water of the delta was crystal clear, and I had a plastic cup, attached to my belt, with which I scooped up cup after cup of the delicious, sweet water as we went along.

Back on campus, I worked hard, and played harder. I’d made friends with some post grad students, with whom I went hiking, and we had many late-night parties at the postgraduate club, as well as intense debates about anything of interest.

Another lasting memory of daily campus life was that of a bare footed student who was accompanied each day by her big, fluffy sheep dog, Maya. Whilst the student attended lectures, Maya would wait patiently for her, playing in the ponds, and running through the grounds, greeting people, and amusing herself. She was a much-loved member of the Wits “family” in those days, and brought me much joy and happiness whenever I had the chance to connect with her. Each day, when home time came, Maya would be lying in the shade, ready to run off home with her human companion. I think it was even suggested that Maya should receive an honorary degree, for all the time she spent on campus, but I’m not sure if this ever happened.

The Hare Krishna society must also be acknowledged, as their members often came to give out beautifully prepared vegan delicacies on campus, (free of charge), which were exotically captivating to the palette, and I remember them to this day.

I also must make mention of the Campus Health Service. This free service was staffed by students for students, and I found it to be of an extremely high standard. The practitioners never turned me away, and were highly dedicated and passionate about the assistance given. I was even treated once, for psychological lock-jaw, caused by extreme stress, which took several consultations to resolve, during which time the physio had to put her gloved hands into my mouth, and massage my jaw joint, until it eventually released the “lock”. I was so grateful to that skilled, kind lady for helping me.

Another much loved pastime, was sitting in the senate house concourse, and starting up vibrant conversations with other students, about many interesting topics over the years. This place was known as our University of Life, and we all thrived there.

I really enjoyed most of my lectures, and especially those at the school of social work, headed by Dr Brian Mckendrick (PhD 1980), who had written several books on social work practice. Dr Wilma Hoffman (PhD 1976) was also a highly respected lecturer, and Dr Leila Patel (PhD 1992) was also a memorable lecturer on community work, as was Mark Anstey (BA 1975, MA 1980, PhD 1981), on group work. We were also privileged to have several sociology lectures by Clem Sunter, who would always challenge our thinking patterns in highly dynamic ways. His “High Road, Low Road” scenario planning discourse still has relevance today, and is still discussed quite often by radio station talk show hosts and the like.

A personal highlight was my social work practicals, because we got to interact with real people, right from the beginning of our training. I was paired with another social work student, and we travelled to “Our Parent’s Home” in Sandringham twice a week. Most of the elderly residents just wanted to talk, often complaining about their fellow residents, but they also wanted to listen to old records from their youth, singing along heartily, and even dancing a little, when the rhythm grabbed them.

Another practical assignment was at the Society for the Civilian Blind, where one of my clients was a young man, a little older than me, who was totally blind. Our counselling sessions were very varied and interesting, but what amazed me most, was that when I went through some deep personal trauma, he asked to touch my face, and said: “Who hurt you? Why have you been crying?” He heard something in my voice, then verified it with his sense of touch. That experience opened my eyes in more ways than one, about the intense sensory powers of non-sighted people.

I was then placed at the Houghton Hospice, where I was assigned to counsel a lady who was terminally ill with cancer. She had two children under 13 years of age, (a boy and a girl), and wanted to spend quality time with them before she passed away. The first thing she said to me in our initial meeting was: “I hope you’re not coming to tell me about the stages of death and dying, because I’ve heard enough about that”. Of course, that was one of the things I was prepared to talk about, but I answered that we could talk about anything she wanted to discuss. Our conversations centred mainly on how her children, and her daughter in particular were going to cope after her passing, and how much guilt she felt at leaving them behind, even though she had made appropriate arrangements for their care. I realised an important truth right then. It wasn’t possible or important for a counsellor to have the perfect answers, but to provide the traumatised person with an opportunity to express their honest feelings, and their deepest fears, to face them, and choose to let them go. In this way, there is a possibility of deep, inner healing, and a lasting feeling of peace.

I also acknowledge the massive contribution to my life, of the Charles Stephen’s Bursary Trust Fund, which paid all my tuition fees for the four years I studied at Wits. Without this assistance, my mother would not have been able to send me to any institution of higher learning. I am deeply indebted to this trust fund, and the Anglo American Chairman’s fund, for subsidising many of my text books, and petrol money to get to my practical placements. I also worked on weekends throughout my varsity years, waitressing, baby sitting, and house sitting. I do try to “pay it forward”, whenever possible, by engaging in pro bono work of different kinds.

I would like to give sincere thanks to Wits University, and particularly the school of social work, which provided me with many rich life experiences, and a solid grounding in the practice of social work, for which I am eternally grateful. I use my skills each and every day, with passion and purpose, to assist each and every person who seeks my help.

-

Silke Heiss

“He who would do good to another

must do it in Minute Particulars.” – William BlakeSilke Heiss (BA 1987, BA Hons 1988, MA 1993) writes:

What can I donate as a contribution to the Wits Centenary celebrations?

My greatest store of wealth are language and literature, so I venture a written weave of a few memories as tribute.

I was not a well cookie when I registered, in 1983, first for a degree in the dramatic arts, a year later downsizing to an ordinary BA I made use of the psychotherapy sessions available through the psychology master's programme and ended up "surviving" from one weekly session to the next, in the care of a gentle soul, who was there to listen for several years to my private anguish, at a token rate I could afford. At the same time he gained what I hope was valuable experience!

That service, and Campus Health, are not what springs into people’s minds when they think of the ivory tower and the illustrious careers it is intended to spawn – but students bring their lives to that "tower", and if the structures can respond appropriately to those lives, they arguably fulfil even more fundamental needs, albeit in the form of a "fringe benefit" rather than an obligation.

My undergraduate and honours years were shadowed by several States of Emergency declared by the Apartheid State, and violent operations beset the townships as even young male immigrants were forced to join South African-born conscripts to fight a civil war against their will. In this context, "Liberation before Education" became a dangerous slogan, and a number of education programmes emerged, facilitated by foreign donors, to protect schoolgoing children. I reached a stage where I was adamant that I needed to join Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s military wing, in order to stand true to my conscience, or fury, perhaps, rather. (I’d had eight armed soldiers, headed by the feared Colonel Whitecross, questioning me in my room, where, at 6am, I was still in my nightie.)

However, one of the fellows in my commune was busy on a doctoral thesis in Theology – he was none other than Thomas Equinus, who penned the wonderful racing columns for what was The Weekly Mail at the time. We knew him simply as Jeff and he spent the better part of an entire night trying to dissuade me from joining MK. And he succeeded! Most beautifully, his main argument was that I might not have the strength not to betray my friends if I were caught and tortured. What a memorable encounter with a true human being!

So, instead of taking up arms, I decided to teach for one of the education programmes, which had the use of the university premises each Saturday, to host a selection of pupils from Soweto. Again here, the university was responsive to the life around it, even while I was – in virtue of studying English as well as a bit of German literature in depth – learning the concepts and vocabulary to discuss what it means to have a human soul, and how deaf, blind and cruel human society often is to it.

JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of The Rings infused my dreams for weeks on end with its vivid narrative of the balance between good and evil, and William Blake’s wise old bard in Songs of Innocence and Experience remains a figure I continue to aspire to embodying. As for WB Yeats, his lines from Sailing to Byzantium (studied in 1985)

A […] man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dressIt directly influenced an SMS quip to my poet husband in 2010, namely, “Why deny my body a-tatter, / when spirit is the greater matter?” – words, which nine years on, formed the title for my first solo collection of poems, Greater Matter. Literature truly weaves the history of the human imagination!

My circle of friends were involved in a variety of fields of study in the Humanities, including classics, anthropology, African languages, French, Afrikaans, politics, linguistics, education and sociology.

In them I felt, directly, say, the pain of being born gay into a culture that not only scorned and denied this proclivity, but where it was still a criminal offence – if you were a man – to act on your carnal love for a person of the same gender. I felt the indignity and hurt of being racially classified as "of lesser human worth", the ultimate dismissal arguably being the classification "Other" "coloured"; and of being forcibly moved – through direct contact with folk who’d not been classified "white".

One friend bore the injustice of his Islamic marriage rites not being legally recognised. Another was at one point going through the process of reclaiming her original Jewish surname, which her father had dropped, in order to become more employable.

As for the traumatic after-effects of conscription – my white male friends would return to this topic obsessively, mulling through memories of physical abuse, one witnessing a violent suicide; or enduring chicanery and calculated boredom; to this day, the nightmare of conscription remains an inescapable presence in my personal life and relationships. How potent is such learning alongside academic lectures!

Notwithstanding all trauma, though, I’ll own that a favourite theme of conversation was sex – proof, perhaps, of our will simply to live in joy? Yet, our table in the Senate House Concourse was no less instructive to me than any of the lecture halls or seminar rooms, as I experienced, through my friends, the ‘minute particulars’ of the general course of history.

What took place in those halls and rooms was similarly mediated by exceptional human moments. A lecturer in Drama & Film, whose first words to us were, “Films are dreams,” planted the seed that allowed me, as the poet and artist I would become, to read the book of life and its mysteries – by using vocabulary I was given by him and his colleagues over a period of three years – allowing me, eventually, as a writer, finely to articulate the moving images that make our world, as much off-screen as on. The most repeated comment my readers today make in response to my poems is, “I feel as if I am there!” – credit for this may well be due, at least in part, to my studies in Radio and Film.

One lecturer, whom I wish to single out in this tribute, is Reingard Nethersole. She founded that short-lived gem, the Department of Comparative Literature, where I did both my honours as well as master's degrees and where I learned, through the close study of structuralism and other literary theories, to discern the human use and abuse of language. Reingard was one who saw the essentially unacademic soul I was, needing urgently to apply in practice all theoretical knowledge I was fed. Her open mind and heart marked an exam, in which my stubbornly creative spirit had presented a debate between two literary theorists – literally in the form of a dramatic dialogue! Her preparedness to accept the surprise and award a mark to such an unconventional answer was testimony to her own flexive spirit; she was, furthermore, instrumental in initiating the interdisciplinary talks, which the university began to host at a time when the faculties and disciplines were still very isolated from, indeed, ignorant of and, at times, arrogant about one another.

I kindly ask my reader to take this sheaf of recollections for the thanks it means to convey to the oceanic institution, in whose currents I floated as but a minuscule bit of plankton for some time. I remain as happily insignificant, but spiritually richer, far more fulfilled!

I’d like to end by serving Wits staff and students a greening thought, as expressed in some lines from a poem of my own –

those days in the sun

on the bench and in the William Cullen Library

our company discipline and our love

for others.

– from Company Discipline, published in Gold in Spring, Ecca Poets, Hogsback: 2016, ISBN 978-0-620-72983-3*

* The entire poem is a personal tribute to a deceased friend, a student, at the time, doing his Linguistics Honours –

Company discipline

To Cliff Speechly

Luck has had me

Luck has had me

today find opportunity

to alight on the bench we used to share

in the shade of smooth-skinned trees

before a circular fountain

splashing now as it did then, thirty-odd years ago,with the comical gestures

water thrown upward

performs.I remember you here

chuckling about us and our human comedies

without cynicism,with the heart you died of

in that wide chest of yours

our gay friends swooned over.We’d sit, chat, chuckle, eat,

then return into the library

to quiet, intense work.It was our company

discipline

as luck would have it.My concentrated heart

remembers your expansive one,

remembers those days in the sunon the bench and in the William Cullen Library

our company discipline and our love

for others. -

Tracy Blues

Tracy Blues (BA 1987, PDE 1987, HDipEdAd 1989, MEd 1995) writes:

When I started at Wits University in 1983, I was still a child. Just 17 years old so I couldn’t drive or do any adult things. I lived at home, a naïve young white girl doing a BA in English, history, linguistics and psychology. I still remember my first ever assignment was for English. I wrote it in fountain pen on lined paper. I joined University Players (the amateur dramatics society) and the End Conscription Campaign. I was a pacifist vegetarian who didn’t believe in violence of any kind and Wits opened my eyes to a whole new reality.

Over the years of my BA, I was teaching part-time in a programme to help matric students in the townships. It began as a way to earn money but soon developed into a passion. I had found my vocation. My BA studies continued against a background of struggle songs, mass meetings at the Students Union, Library Lawns or Great Hall and running from the police and their stinging teargas.

When I completed my BA, I did a post-graduate diploma in education so I could teach at high school. Moving to the Education Faculty involved changing campuses to the newly built West Campus. It had good facilities but there was no social heart so I would return to my old hangout: Senate House Concourse. There I got to discuss every possible subject with a diverse group of students and staff from many different faculties. It was there that I made many lifelong friends including one who became my husband.

While I was studying towards an HDipEd and then an HDipEdAd (post-graduate diploma in adult education) I was working as a part-time researcher at the Academic Staff Development Centre on a research project into teaching and learning at Wits. The centre's offices were in Senate House so it was easy to go to the Concourse in any free time. The friendships and debates flourished.

I decided to continue my studies with an MEd looking at the use of drama in facilitating adult education. This saw more change: from being a full-time student to being a part-time one. There were also changes at home. I had a full-time job as a teacher and I married one of my Senate House Concourse friends. He was doing a PhD in mathematical modelling of biological systems and through him I got to see the inner workings of a 24-hour laboratory at Wits Medical school. I learned about genetics and oncogenes and then the effects of the Group Areas Act.

My husband is of Indian descent and I am of Scottish descent. The mixed Marriages Act had recently been repealed but the Group Areas Act was still in force. We were legally married but could not live together without breaking the apartheid law. We were evicted from our flat in Yeoville for contravening the Group Areas Act and eventually found a home to rent in Mayfair through another Senate House Concourse connection.

Through the heady days of the transition to democracy I worked on my MEd doing a research project in rural Limpopo. No matter how far afield I went, I always came back to Wits. By the time I graduated with my master's in 1995, I had spent 12 years at Wits and transformed from an idealistic teenager in Apartheid South Africa to an adult trying to find their way in a new democracy. Now, thirty years later, the man I met on Senate House Concourse and I are still married, we are still friends with our Concourse compatriots and I still use the skills I learned at varsity. I owe Wits a debt of gratitude for my multi-faceted education.

-

Gesche Heiss

Gesche Heiss (BSc 1989, BSc Hons 1990, MSc 1992) writes:

After my twin sister and I matriculated, we started at Wits University in 1985. I still remember my student number: 8555629. I’m not good with numbers, but this number has been deeply rooted in my mind, with many positive memories attached to it.

My twin sister and I would regularly visit Senate House for lunch, enjoying our avocado three-inches, Chelsea buns and strawberry or banana-flavoured yoghurts, called Sippity. Senate House also provided the self-service vendors, when sometimes sweets or treats would get stuck in them. Back then they were coin-operated, we did not use cards.

My twin sister and I loved listening to lectures, diligently taking notes, with pens flying on paper at considerable speed. I felt relaxed in the familiar lecture halls, the smell associated with them, and the steep, amphitheatre-like fixed, wooden benches with their hard, narrow desks. Studying for a BSc, we would listen to physics, maths, chemistry, microbiology, botany and zoology lectures, and more, of which the latter three were my favourites.

Because of apartheid, we were all white students, there were no students of colour, except for one young man in the zoology class, whom I admired. I would look at him intently for longer periods of time, perhaps I smiled or we greeted each other, but not many words were exchanged. He would regularly wear a suit, usually a smart light beige; that I remember.

The microbiology lecturer inspired me to continue my microbiology PhD later on in Germany. His hair was shoulder length, curly and bright orange. He was Scottish, and I will always remember his voice and Scottish accent. His lectures were so lively and awe-inspiring.

Our immunology lecturer was a chaotic man, or was it just the speed with which he lectured? I learned a lot from him anyway. Our botany lecturer would have her overheads with small writing and read those to us. That was also an individual style of lecturing. Our bacteriology lecturer would have her head bobbing about sideways, like those toys with bobbing heads. I appreciated her well-ordered lectures, though she was strict when it came to project work.

We would regularly have practical classes in the afternoons – the rat and frog dissections made it clear to me, that dealing with animal experiments was not my path.

Our honours year was a very busy one. I chose bacteriology and immunology and steadfastly devoted myself to my projects, while watching my sister with hers, in wonder. She would have such fun with her virology, performing her pink ethidium bromide phenol-chloroform extractions to extract virus.

My isolated bacteria became contaminated with Bacillus subtilis, so it was an interesting venture to determine what it was that was overgrowing my delicate cultures, though I completed the project with success.

Our cell culture required completely sterile working, which meant we’d use alcohol and Bunsen burners to sterilise the mouths of the bottles and tissue culture flasks. At times the alcohol would cause the laminar flow (sterile working unit) to go up in flames, so you had to take care of that not happening again. Being students, we’d have water spray games in the laboratory, and play games with the latex gloves, including gloved hands going up in flames! The moral of the story: Don’t use so much alcohol to sterilise. It was great fun.

My MSc microbiology project was quite big, I think to this day, it could easily have merged into a PhD, though I chose to travel to Germany for that. Xavier (I love the name), an older student, would watch me working in the lab, and we’d go ride on his motorbike and have soft serves with caramel. His girlfriend had a fear of apples. Her fear was that she might swallow a pip and that a tree would grow in her gut. I hoped I could nullify those fears for her on a braaivleis party. Xavier, on the other hand, cautioned me that I should always keep my coat hangers in alternating, varying directions in my cupboards. He told me it would stop thieves from stealing my clothes. I suppose he had a point.

Three-quarter of the way through my MSc, I chose to do another in biotech. We were a group of four and our visit to the Centre for Scientific and Industrial Research was highly impressive, with agar plates poured and bacteria counted.

I met my boyfriend in the MSc biotech class. We’d fool about in the biochemistry and genetics class, washing our feet in the high laboratory sinks, while the biochemistry lecturer spoke of “the snags of science”, and we’d make fun of the names of the restriction enzymes, example Sau3A. My genetics lecturer, whom I’m still friends with, said I should “stop acting like a schoolgirl”, but I couldn’t stop laughing. He himself called the one enzyme “the notorious FokI”. My boyfriend was half-Dutch, half-German, and so we travelled to Germany together, in pursuit of our PhDs.

-

Rashad Bagus

Rashad Bagus (BAEd 1989, MAEd 1992) writes from Johannesburg about his "beloved alma mater"

I have been extremely fortunate to have been associated with you for close to 40 (of your 100) years as a student and as a member of staff and today I want to pay my tribute to you for providing me with two incredible gifts: my humanity when I was labelled “a non-white”, and a group of friends who not only enhanced that humanity through their unconditional acceptance of me, but who also educated and helped me eventually to pursue a career in your hallowed halls.

This group who sat and conversed, smoked, drank coffee, ate toasted Chelsea buns, laughed, cried, fought, debated, and engaged with knowledge daily, was labelled by a member of the group as “The Senate House Committee for Higher Learning” - how apt a label.

It was in this group where a naively innocent, working-class township boy who was brought up in a conservative home, received his real education from social and political scientists, geneticists, philosophers, psychologists, theologians, engineers, artists, poets, lawyers, mathematicians, linguists, drama and film aficionados, and numerous others. Here it was that I was first confronted by individuals who had a sexuality different from mine and who challenged what society considered to be “normal”, other individuals who were hard-nosed atheists or committed believers, free market proponents, liberal, social-democratically inclined individuals, and radical socialists who constantly disagreed about what a future society should look like. Where else could one be exposed to so many influences and domains of human knowledge?

In Senate House I sat over the years reading, the often censored, Wits Student and the exploits of the eternal student, Nurden, and witnessed the protests, the incredible singing of protest songs in Senate House, the apartheid police’s invasion of the campus, the teargas, the attaching of plaques on the wall outside The Great Hall to protest the Apartheid’s state numerous policies, the assemblies of the university community to protest police brutality and the policies of the Apartheid state and Prof Tobias’s speech with its immortal refrain, “The Senate is angry . . . “, the cordon of academics formed around students to protect them from police attacks, the rubber bullet which hit one of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor’s, Prof Mervyn Shear, and the now legendary response to the police’s attempt to intimidate the university community with a helicopter flying low over one of those assemblies when some students formed the words “F*** Off” with the chairs on the Library Lawns, the regular stand-offs between a pro-government student organisation and the NUSAS-affiliated student organisations, the debates about academic freedom when even the presence of anti-apartheid academics visiting Wits was challenged, the continuous debates between the MSA and SAUJS on the question of Palestine, the establishment of the Black Student’s Society despite the common pursuit for non-racialism, and so much else. Where else could one have experienced so many historically important events?

In Senate House I sat over the years reading, the often censored, Wits Student and the exploits of the eternal student, Nurden, and witnessed the protests, the incredible singing of protest songs in Senate House, the apartheid police’s invasion of the campus, the teargas, the attaching of plaques on the wall outside The Great Hall to protest the Apartheid’s state numerous policies, the assemblies of the university community to protest police brutality and the policies of the Apartheid state and Prof Tobias’s speech with its immortal refrain, “The Senate is angry . . . “, the cordon of academics formed around students to protect them from police attacks, the rubber bullet which hit one of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor’s, Prof Mervyn Shear, and the now legendary response to the police’s attempt to intimidate the university community with a helicopter flying low over one of those assemblies when some students formed the words “F*** Off” with the chairs on the Library Lawns, the regular stand-offs between a pro-government student organisation and the NUSAS-affiliated student organisations, the debates about academic freedom when even the presence of anti-apartheid academics visiting Wits was challenged, the continuous debates between the MSA and SAUJS on the question of Palestine, the establishment of the Black Student’s Society despite the common pursuit for non-racialism, and so much else. Where else could one have experienced so many historically important events? There were also lighter, but equally memorable, times. The raucous Orientation weeks and the Academic Freedom lectures which were always an important part of the Orientation week, the spectacular sight of the student parachutists of the Wits Flying Club’ landing with precision on the library lawns, the Free People’s Concerts staged by the Wits SRC on the final day of the Orientation Week where I saw Johnny Clegg and Juluka for the first time, the SRC election circuses and the elections (I still want to know who was the candidate Zot Zyblotsky, the anonymous robotic character, who stood for election on one occasion?), the Rag floats and the Rag Magazine sold on the day when the rag procession snaked through the streets of Johannesburg to raise money for charity, the engineering students’ risqué Torque magazine with its page three female “nudes” and the outrage this caused within the university community, the Wednesday lunch time performances by students from the School of Music and the student art exhibitions in the Wits Arts gallery. Where else could one experience so many cultural activities?

There were also lighter, but equally memorable, times. The raucous Orientation weeks and the Academic Freedom lectures which were always an important part of the Orientation week, the spectacular sight of the student parachutists of the Wits Flying Club’ landing with precision on the library lawns, the Free People’s Concerts staged by the Wits SRC on the final day of the Orientation Week where I saw Johnny Clegg and Juluka for the first time, the SRC election circuses and the elections (I still want to know who was the candidate Zot Zyblotsky, the anonymous robotic character, who stood for election on one occasion?), the Rag floats and the Rag Magazine sold on the day when the rag procession snaked through the streets of Johannesburg to raise money for charity, the engineering students’ risqué Torque magazine with its page three female “nudes” and the outrage this caused within the university community, the Wednesday lunch time performances by students from the School of Music and the student art exhibitions in the Wits Arts gallery. Where else could one experience so many cultural activities?While witnessing all these incredible things I also had the immense privilege of attending lectures by numerous academics of repute who further shaped my knowledge and understanding of the world. Then, as a confirmation of the knowledge that I had gained, you accepted me into your bosom by appointing me as a tutor and retaining my services until I retired in 2021. I have therefore been given the rare opportunity to experience you as an “outsider” and as an “insider” and in my long association, you have truly been a “nurturing mother”. May you remain that for future generations of students as well.

Happy 100th anniversary my beloved alma mater. May you have many more.

Gratias aeternas

-

Nina Heiss

Nina Heiss (BSc 1989, BSc Hons 1990, MSc 1993) from Darmstadt, Germany, writes:

I studied at Wits University from 1985 until 1992. These were busy, fun, and engaging, years during which time I completed my BSc, honours and master's degree.

I loved the spacious campus, the amphitheatre-like stairs, the large lawns full of students, and the pool. My mother who worked in the chemistry department swam regularly in that pool. Altogether the campus left an atmosphere of natural space and freedom. The sheer multitude of beautiful buildings and the breadth of faculties from science to arts to engineering made the campus unique. How lucky and privileged we were to learn, love and absorb life in this special place.

I loved the spacious campus, the amphitheatre-like stairs, the large lawns full of students, and the pool. My mother who worked in the chemistry department swam regularly in that pool. Altogether the campus left an atmosphere of natural space and freedom. The sheer multitude of beautiful buildings and the breadth of faculties from science to arts to engineering made the campus unique. How lucky and privileged we were to learn, love and absorb life in this special place.The warm and genuine people that I met at Wits left a lasting impression on me. They were interesting people bringing in flair, knowledge, creativity, pizzazz, personal engagement and commitment. Our lecturers were personable people. To name just a few anecdotes: My genetics lecturer was a strong woman who taught me a lot about the wonder of genetics and sparked my interest in this field (besides, she kept lovely talkative Siamese cats who scooped milk from the milk can).

I enjoyed the lecturer who had a passion for mushrooms and convinced me that mushrooms can supply the world with sufficient protein if grown properly. During my honours project work, my virology lecturer Chris, who was a fun person to be with, took me on an unforgettable trip in her little bus to pick cassava leaves for a couple of days. The idea was to extract and identify the Cassava virus which is a frequent hassle and hampers the tuber from being a source of food in hot dry climates. To this day mushrooms and cassava fascinate me (we cook and enjoy eating them – cassavas for instance taste delicious in soups).

Another experience that stuck with me was my biology lecturer who adopted a two-year old girl. The couple conveyed their story in a beautiful and natural way and their happiness was infectious. We were invited to their home to celebrate, and there was the daughter running about the room laughing.

Apartheid played a big role. Even though I found it enriching and am still proud to have been at a university attended by a variety of cultures and people at that time, we seemed to tip-toe around each other rather than getting to know each other. To this day, I do believe we missed out by not making friends more easily. I found it shocking and sad that some pupils could not come to university at times because of riots and for fear of being injured or killed by stone-throwing. Then there were demonstrations on campus with teargas and police. My elder sister went to these demonstrations while my twin-sister and I continued our studies (it felt ominous and not right to not participate but I think we were scared). Generally, the demonstrations must have been effective with the political changes that then followed.

I loved the campus library. We spent many hours studying, removing journals, copying pages at great length, chatting, as well as eyeing out the boys. Later on, we were impacted by sanctions meaning that among other things, certain laboratory orders and ordering reprints took months until they arrived. This taught me to improvise and not to take anything for granted. The fact that we could not carry on with our research effectively (our scholarships were cut among other things) and with the brain drain, I decided it was time to leave.

I enjoyed my years at Wits and am thankful and grateful to have been there and to have met special people and friends for life.

Thank you for the opportunity to contribute to the Wits Alumni Centenary celebrations.

-

Dr Jeffrey Zerbst

Dr Jeffrey Zerbst (BA 1978, PDE 1978, BA Hons 1983, MA 1986, PhD 1993) writes how Wits "saved his soul":

In the 1970s and 80s, Wits stood out as a beacon against apartheid. It contained many fine academics who stood for free enquiry, reason, truth, and justice. It was a blazing triumph of liberated thought standing against the shibboleths of the cruel and perverted regime running South Africa.

My liberation, though, was not of the political kind. I needed no conversion there. It was of the religious kind. I entered Wits as a devotee of a religion that stood proudly against “the wisdom of the wise” and which demanded assent to the unfounded claims of one Paul (born Saul) of Tarsus, who had raised to the status of a god a man from Galilee crucified by the Romans for sedition. This religion called Christianity was, oddly, embraced by many of the supporters of apartheid, and by even more of its opponents. It held many within its bosom and was their ultimate beacon of light.

My liberation, though, was not of the political kind. I needed no conversion there. It was of the religious kind. I entered Wits as a devotee of a religion that stood proudly against “the wisdom of the wise” and which demanded assent to the unfounded claims of one Paul (born Saul) of Tarsus, who had raised to the status of a god a man from Galilee crucified by the Romans for sedition. This religion called Christianity was, oddly, embraced by many of the supporters of apartheid, and by even more of its opponents. It held many within its bosom and was their ultimate beacon of light.I felt uncomfortable in its clutches, and found, at Wits, a Biblical and Religious Studies Department, which taught religion in a spirit of openness, and which laid out the scholarship treating the Bible as literature and not as a doctrine to be followed. Bathed in the hallowed light of textual, source, form, and literary criticism, I found, at last, rational, scholarly approaches to the biblical tradition which prised open the fissures on my faith and changed me, in a few thrilling months in my second year, from a Christian to an Agnostic. I was, at last, free of the burden of believing things that simply did not make sense.

Most of my lecturers were still people of devout faith, but their beliefs were of a more sophisticated kind. They were able to reconcile their belief in God with the findings of biblical criticism. I could not do this. Since Christianity is based on orthodoxy, not orthopraxy, I needed to hold fast to fundamental beliefs if I were to continue as a faithful member of the Christian community. I found, however, that those beliefs had been significantly eroded.

The freedom I felt was exhilarating. I continue to experience it as I dive, ever more deeply, ever more assiduously into the topics of Philosophy of Religion. This is my chosen subject area, my source of intellectual passion, my source of investigative joy, the orchard where my striving, toiling self goes to cultivate its knowledge and prune its passionate statements of conviction, and religious non-belief. There I am my true self. There I am happy. Wits taught me what I need to be here.

Of course, since I have no faith in resurrection, or a supposedly perfect god who made an imperfect world shot through with pain and suffering, I have no recourse to hope for my personal survival. As a non-believer, I am psychologically bound by the lessons gleaned from my research. As a deeply alienated being in the human sphere, I could – if I allowed it – find solace whispering in my room to an imaginary friend whose succour has comforted many approaching the sandy scrapheap of oblivion. I will not, however, embrace that balm for the barmy.

The Church showed me one universe of meaning. Wits showed me another – one that depended on reasonable assent to propositions. In this second universe, I became convinced that there is no soul to save. The soul is but a metaphor, and – I contend – so is the mind. Let the soul stand for the core identity we cling to amidst the constant shifts in our evolving, febrile, unstable consciousness.

My metaphorical soul was saved many years ago at Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa. I am grateful. I walk in the footsteps of demonstrative truths. I reject wishful thinking, superstition, and accumulated traditions built on evidential straw. “Bible belts” are conveyer belts to profound irrationality.

To my alma mater, I pledge my love. It may not radiate for long, but it is the love of a true believer, and a passionate discipline of doubt. We can know only what we know.

-

Harold Shapiro

Harold Shapiro (BCom 1967, CTA 1970) writes:

In 1965 I joined the local AIESEC-Wits committee (AIESEC is a global platform for young people to explore and develop their leadership potential). I became the local AIESEC-Wits President in 1966 and attended the AIESEC International Conference in Tel Aviv in March 1966.

The one picture is the local AIESEC-Wits Committee in 1965 together with a few of the exchange trainees at the time.

The two pictures of the AIESEC International Congress in Tel Aviv , some 55 years ago in 1966, show how times have changed. Everything was paper. Potential trainees completed application forms which were submitted to the local AIESEC committees. The best students were chosen. Similarly, companies willing to take foreign trainees for a three-month period, such as SA Breweries, also completed information forms.

Then, at the conference, each country member had a table, and delegates would go from table to table trying to arrange swops. At that time the USA was the number one destination for trainees so they had the pick of the bunch. I became National President of AIESEC South Africa in late 1966 and we had a lot of great initiatives to get companies to provide traineeships. The issue we now had was that AIESEC SA was only English speaking universities. There was not much trust in those days between English and Afrikaans universities. We started off with Tukkies and spent a long time trying to ensure that AIESEC was apolitical, and convincing the Tukkies commerce delegates that AIESEC International was also apolitical (which it was in those days).

Finally, after months and months of negotiations we devised a constitution that was agreed on by AIESEC-SA and the Afrikaans universities. They joined AIESEC-SA to form a national body. We managed to get Dr Frans Cronje, the CEO of SA Breweries, to be our Honorary Chairman, and got the Minister of Finance, Dr Diederichs, as Honorary President.

AIESEC -SA grew into one of the largest of the countries offering exchanges and our offerings were well received at the 1968 international conference in Istanbul, which I attended.

Having Dr Cronje as our Honorary Chairman came in very handy when, sometime in 1968, Witsies were protesting on Jan Smuts Ave, (opposite Pop’s), a whole bunch of Hell’s Angels had parked themselves in the SAB premises waiting for the opportunity to climb the walls and attack the students with chains. I called Dr Cronje to warn him. He told the police to get the thugs off SAB property. They still charged but everyone had time to run.

Even more handy was having Dr Diederichs as our Honorary President. In late 1968 we had a special exchange group of German commerce students. I was doing my CTA final year after completing my BCom at end 1966. I’d left the swotting a bit late and was relying on the two weeks swot leave I had from my accounting firms to be ready for the exams. The phone rang at my home, and our full-time secretary on the Wits Campus said that the Special Branch had arrived and were going through all our files. The head of the group took the phone and asked me to meet them at Jan Vorster Square that afternoon. I had no idea what it was about.

I duly arrived and went into a room with large wooden tables adjoining each other. Spread across the tables were pictures of a Wits protest on the pavement at Jan Smuts Ave.

The head man asked me to look at the pictures and identify the persons circled in pen. They were all AIESEC German exchange students. He asked me what they were doing there. I told him honestly that I had no idea.

The SB knew that Dr Diederichs was our Hon President and said that they didn’t want to create an international incident but he wanted me to get their passport numbers.

What a pickle I was in. I was very uncomfortable approaching the foreign students and fortunately before I could make a decision, it was decided for me.

On the weekend, the Sunday Express had a front page story, provided by the German students about their reason for participating in the protest and the fact that the SB was seeking to get their passports. I had no comment except that we were a non-political organisation.

I heard no more from the SB, but my swot leave had been ruined, and for the first time in my life I had to repeat a year.

I couldn’t afford to lose another year, and in 1969 resigned my position as National President.

I have very fond memories of those years and I learned a lot from the experience.

I passed the year, and my Board Exam!

-

Phyllis Hyde

Phyllis Hyde (BA Hons 1956) writes:

When I was working in the Faculty of Arts and before the introduction of computers, when we wanted to find out how many students were registered for a particular course, the system was as follows:

We had square cards with all courses offered in the Faculty printed around the edges topped by a little hole. Each student’s name was typed onto a card and the hole of the courses for which he/she was registered was clipped open with a clipper similar to that used by tram and bus conductors clipping passengers tickets!

These cards were housed in shoe boxes. When we needed to know how many students were registered, for example for English 1, we would take a knitting needle, pass it through the hole of English 1 of all the cards in the box, lift up the needle with the cards hanging on to it and drop them onto the table. We would then count the cards and this would give us the number of students registered for that particular course!

And do you know how exam results were prepared for publication? All done by hand – every single result for every student was entered onto a sheet with the students’ names and courses on that sheet – very laborious and time consuming.

And not to mention how we obtained the matric results for our applicants. One of our members of staff lived in a flat opposite Wits and on her way to work she would pick up the newspaper from the seller on the corner and we would wade through all the matric results to find which of our applicants had passed matric. Then one of the members of staff in the Faculty of Commerce would go to Pretoria to the Department of Education armed with the names of all the applicants to the Arts and Commerce faculties, and spend a few days there laboriously copying out the results for every subject each applicant had written. Based on these lists, we would select the successful applicants.

When the first computer was introduced we didn’t trust it, so for two years thereafter we continued simultaneously with these systems until we were satisfied that the computer could be trusted!

When the first photo copying machine arrived and was placed in the foyer outside the Great Hall, to make a copy one had to insert a 5c coin.

One day the Professor of Classics came to me and asked me to help him make a copy of something. He gave me his 5c coin and I told him to watch what I was doing so that he could do it himself in the future. But the dear old man, so steeped in ancient Greece and Rome could never master this system and came to me for help every time he needed to make copies!

One day the Professor of Classics came to me and asked me to help him make a copy of something. He gave me his 5c coin and I told him to watch what I was doing so that he could do it himself in the future. But the dear old man, so steeped in ancient Greece and Rome could never master this system and came to me for help every time he needed to make copies!I think I had better stop now, as the flood gates of memories have really been opened and I could go on and on and on!

-

Lynette Douglas

Lynette Douglas (BA 1962, DipEd 1986) writes:

Freshers concert was great fun in 1958 we did rock and roll numbers and also the can-can. Womens’ res was the place to be. Mrs Biesheuvel was outstanding at the helm of res. Without naming anyone in particular, we had wonderful lecturers of world renown. My BA has enriched my life for all these years. I returned to Wits in 1985 to do the diploma in adult education. What a rewarding experience. It lead to new openings in my professional training life. I can write whole essays about my time at Wits but must leave something for others!

-

Linda Zulu

Linda Zulu (BHSc Hons 2018) writes:

I am a penultimate year LLB student. I juggled a full time job, a sick father in hospital (may his soul rest in peace) and a full time honours degree at Medical School which was entirely a new field of study to me. What makes it most memorable is that life, on that particular year, really showed me the highs and the lows, trials and tribulations in excess, but still managed to graduate on record time. The photograph (right) speaks volumes.