The 180-million year old quirk

- Professor Terence McCarthy

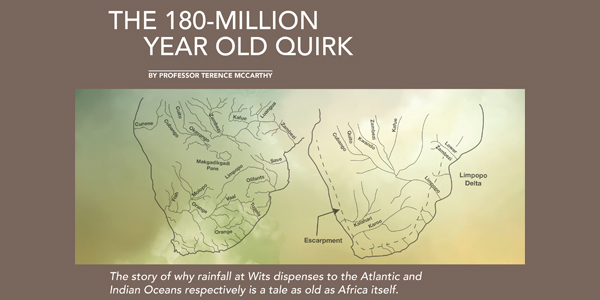

The story of why rainfall at Wits dispenses to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans respectively is a tale as old as Africa itself.

Wits University is located right on top of the watershed that divides the Limpopo and Vaal-Orange river basins. This means that rainwater that flows off the front roof of the Great Hall discharges into northerly draining rivers, ultimately entering the Indian Ocean via the Limpopo River. Rainwater flowing off the back roof, however, flows southward into the Vaal River and is ultimately discharged into the Atlantic Ocean via the Orange River.

This quirky watershed was created hundreds of millions of years ago when the Supercontinent, Gondwana, broke into the continents of Africa, Antarctica, Australia and South America.

The separation of southern Africa from South America to the west and Antarctica to the east resulted in two very asymmetrical drainage systems: The Karoo-Kalahari River System rises far in the east, almost on the eastern escarpment, and flows westward across Africa to discharge into the Atlantic Ocean. The Zambezi-Limpopo System in the north rises along the western escarpment and discharges into the Indian Ocean.

The Limpopo River of today is a small vestige of what it used to be. In the Cretaceous Period (before 65 million years ago), its tributaries included the upper Zambezi, Kafue and Okavango Rivers, and it was the main drainage of southern Africa. It is for this reason that the Limpopo Delta is the largest on the African continent. At that time, the ancestral Orange River (the Karoo River) discharged into the Atlantic Ocean much further south than it does today (near the mouth of the Olifants River), and what is today the lower Orange River was part of a separate river system named the Kalahari River.

These ancient river systems have undergone substantial adjustments since the Cretaceous Period. Crustal warping, (which is the bending of sedimentary strata), severed the upper Limpopo from its tributaries (upper Zambezi, Kafue and Okavango rivers), resulting in the large Lake Makgadikgadi.

The lower Zambezi cut inland and progressively captured the Luangwa, Kafue and Upper Zambezi rivers. Consequently, the size of Lake Makgadikgadi was greatly reduced. In the south, the Kalahari River captured the Karoo River to form the modern Vaal-Orange System.

Notwithstanding these changes, the original drainage asymmetry and the Wits watershed, implanted in time immemorial when Gondwana broke up, remain evident today.

Terence McCarthy is Professor Emeritus of Mineral Geochemistry in the School of Geosciences. He has wide research interests in the earth sciences, including economic and environmental geology, geochemistry and geomorphology, and is a leading expert on the geology of wetlands, especially the Okavango Delta in Botswana. For more on why water from Wits flows to two oceans, read The Story of Earth and Life: A Southern African Perspective on a 4.6-Billion-Year Journey, which he co-authored with Professor Bruce Rubidge in the Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences, as well as How on Earth? by McCarthy and Professor Bruce Cairncross.

Read more about the research conducted across faculties, disciplines and entities to help secure humanity’s most important resource for survival: water, in the fourth issue of Wits' new research magazine, Curiosity.